Artwork is borrowed from a painting by Ali Maimoun

CF: How and where was the mix recorded?

I recorded this mix about a year ago, at my home in Paris, using various Gnawa music materials spanning digital, vinyl, and cassette tapes. Because Gnawa music is originally a highly coded, life practice which takes place in a larger trance ritual involving all senses, the best performances hardly take place in the studio, where these conditions cannot be reproduced. Recordings, which I think only began in the eighties, were produced on cassette rather than vinyl, and some of the best performances were recorded live, sometimes with quite rudimentary setups.

There are some rare, very good recordings but on the whole, the difficulty I – and any Gnawa music enthusiast – face resides in the heterogeneity of the material, whether it concerns the format, quality or nature of the performance. In a way, this mix is the somewhat partial and incomplete result of choices I have had to make, navigating between the nature of the piece, the availability and quality of recordings and my personal taste.

CF: How did you first get involved with music and how did you start collecting records?

Well, I’ve had the chance to grow up in a country where music is everywhere. Whether it be my grandmother sharing her passion for Aita – another incredible Moroccan music genre – through tapes and performances, attending weddings, religious celebrations and processions, or simply passing by corner shops in Casablanca’s Maarif district where I grew up. Morocco has an incredible diversity of music genres, themselves embedded in various social and spiritual contexts. I was lucky enough to be sensitive and curious to the richness and complexity of these pluri-centennial traditions, which musicians and communities keep alive to this day.

One important thing to be mentioned is that as a young boy, I did not – like most Moroccans – consider these music traditions directly as art. As music is often used as an instrument of larger forms of social and spiritual practices, musicians are first and foremost considered excellent technicians – virtuoses of one specific craftsmanship. In fact, one identical Moroccan Arabic term – maalem – designates a Gnawa master and a confirmed artisan of, say, carpentry or pottery. Although this is beginning to change, the difference between art, craft and rituality is more tenuous than what we are used to in the occidental world.

An important moment of my music education was as a teen, when I started listening to hip-hop music. Moroccan hip-hop, especially, was then just starting to become a thing and it felt new and exciting to be following its evolution. Hip-hop also showed me the way into new music genres such as jazz, disco, funk and soul, and taught me to appreciate them.

I do not recall any record shops in Casablanca back then, and what we collected were CDs and tapes. It was when I came to Europe to study that I bought my first records and started DJing at college parties. After a few years in different cities, I moved to Paris, where alongside Souhail and Saad El Amri – two childhood friends – we started collecting records and began We Dig Underground, hosting mixes and interviews with artists like Kai Alce, Damon Lamar and Darand Land.

CF: You also compose and produce your own music, how did you get started and where does your inspiration come from?

Actually, I started when a few years ago my friends gave me an MPC2500 for my birthday. I did not start to use it straight away, for many months I just stared at it, both fascinated and a bit shy. Thanks to my friend Jérémy Deniset’s crucial support and teachings, I began to dedicate some time every day on sampling work, which resulted in “Pêche de vigne”, released in 2018. This was a very valuable experience, and despite the sometimes bad reputation it may have, I think there can be true artistry in working with samples. Over time, and once again thanks to Jérémy, I got interested in musical theory and started composing using the Korg M1, another gift.

One of my ongoing goals has been to incorporate Gnawa instruments like the guembri and crotales in my music. However, I strive to do it in a way that avoids certain pitfalls, like having these instruments overshadowed by other elements or creating layers without musical coherence. It is a delicate balance and I try my best at using these instruments in innovative ways, not because I grew up with them and certainly not because it is trendy to fuse old and modern or European and African but because they keep on moving me in a very particular way. Additionally, I hope to craft engaging rhythm sections, which are very important in achieving the trance state sought after in the Moroccan music traditions, no matter what part of the country you go to, or what local dance/spiritual music/ritual you attend.

Working with this musical heritage plays a great role in my inspiration, as well as late-capitalism city life struggles most of us are confronted with, and – cheesy but true – observing morning and evening light from my window.

CF: You’ve recently launched your own record label, Dawyna Music, what is the concept behind the label and what do you have planned for the early days?

“Dawyna” is a phrase that one can find in the lyrics of various Moroccan music traditions – Gnawa, Aita, and Malhun for example – which are geographically, historically and socially very different from one another. It roughly translates to “heal us” in Moroccan Arabic and in this sense, represents a collective call for healing, which leaves open the question of who/what heals. Although in these traditions and especially in Gnawa, healing is the result of a larger – sometimes straightforwardly spiritual – rituality, music plays a fundamental role in it. Personally, I am convinced that regardless of the tempo or genre, a right combination of notes and rhythm has the power to transport us to a cathartic state which has a healing effect, whether individual or collective. Although of course music cannot be reduced to this, I believe it is an idea that can help us understand a number of music traditions worldwide and the mission of the label is to promote music that somehow possesses this transformative quality.

This summer, a first record, “Excès d’amour”, was co-released with Red Lebanese, who have been of great support all these years. There are already a few artists – who are close to my idea of the label and who I believe we should be hearing more of – that I would like to feature: Serious A, Al from Dockside Records or Jérémy Deniset. I have also finished an album for mastering. One important thing to be said is that I see Dawyna as a collective project, it will and already does rely on the work and creativity of Sophie Vaillant, Pierre-Alexandre Vacherand and Moïra Rosabrunetto.

CF: What do you normally listen to at home? What are 3 of your favorite albums past or present?

At home, I enjoy listening to a wide range of music genres, except perhaps for rock, which I could use some recommendations for! Of course, it depends on the activity I am doing, but overall, I would say a lot of Moroccan music as well as a lot of Black American, Caribbean and South American music.

Three of my favorite albums, which I have been listening to again very often these days are:

3 Chairs – 3 Chairs (Album)

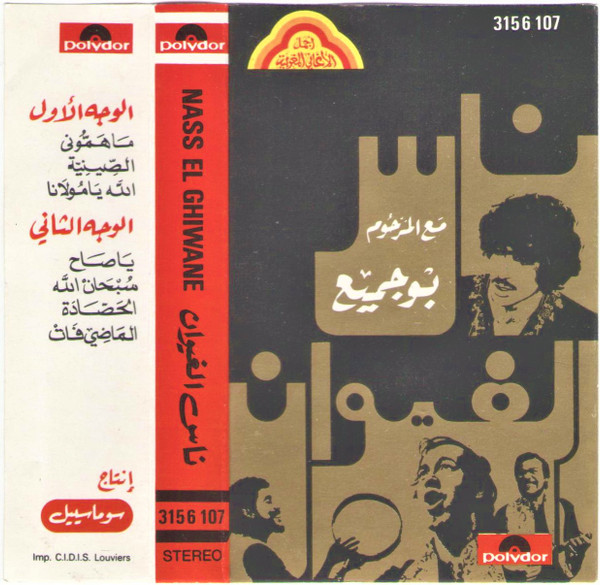

Nass El Ghiwane – مع المرحوم بوجميع (released on cassette tape Polydor – 3156 107)

Maleem Mahmoud Ghania – Untitled” (cassette released on Fikriphone – FP.25)

CF: What are your favourite spots to dig in and around Paris?

Great spots are Superfly and Betino’s. Actually, the latter is a lot more than just a record shop for me, it is where I started to buy records as well as a sort of hub, where I have met many of the people and artists I like. And shout-out to Betino, who has seen me learn to play records and produce, always sharing his extensive knowledge of music and supporting what I do.

CF: Records aside, what’s your favorite thing about living in Paris? What would you recommend to someone visiting for 24h?

Well, aside from music, I am quite passionate about philosophy and especially the writings of Spinoza. In Paris, I can attend lessons and seminars of my favorite professors and great Spinoza specialists. It is also a nice city for food and wine and I enjoy its cultural plurality. What I would recommend to someone visiting Paris would be to simply walk through the city’s streets, taking its beauty in. Maybe stroll through Marché d’Aligre and stop for a coffee at Aouba Torréfaction in the 11th arrondissement. Have a good dinner at La Renaissance in Voltaire, and if you have the chance, catch a jazz or even a Gnawa concert.

Answers edited by Moïra Rosabrunetto